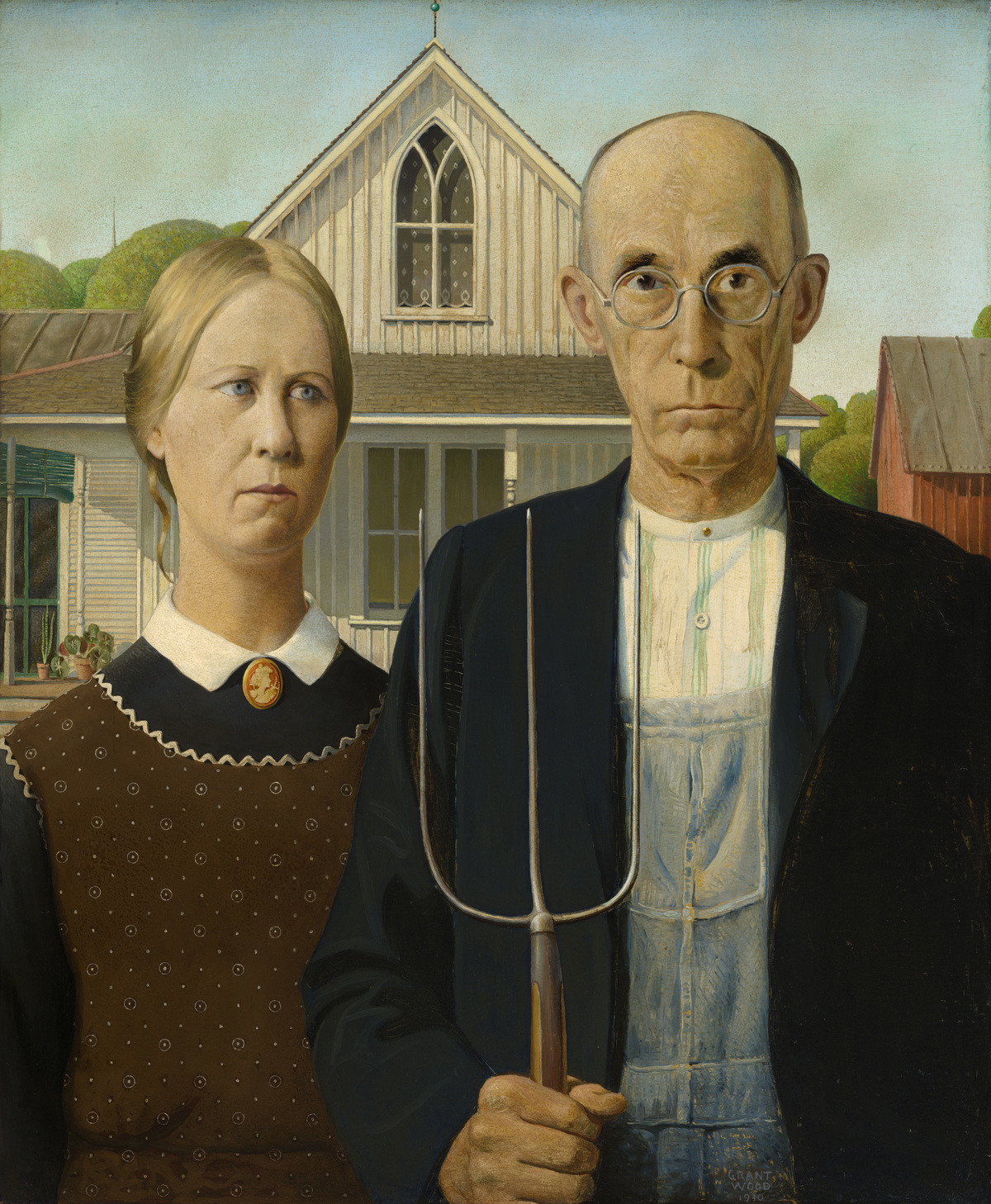

Most people recognize the image:

a stern-faced man holding a pitchfork beside a woman in front of a white farmhouse.

American Gothic, painted in 1930, is one of the most iconic — and most parodied — works in American art. But fewer know the story behind the artist who created it.

American Gothic, 1930. Art Institute of Chicago; Friends of American Art Collection 1930.934

”...Grant Wood was at the forefront, celebrating local culture for what it was, what it had been, and what it could be.”

Joni Kinsey, professor emerita in the UI School of Art, Art History, and Design

Born and raised in Iowa, Wood's work celebrated the people and landscapes of the Midwest

Grant Wood (1891–1942) was born and raised in Iowa. He spent some of his most creative years as a faculty member at the University of Iowa, where he not only painted but also mentored students, explored multiple art forms, and helped define a movement. A skilled carpenter, metalsmith, printmaker, and interior designer, Wood championed Regionalism, an American realist style that celebrated the people and landscapes of the Midwest.

During his lifetime, Wood was featured in Life and Time magazines and was arguably the most well-known figure on the University of Iowa campus at the time. As Professor Emerita Joni Kinsey in the UI School of Art, Art History, and Design explains, “It was an era — during the Great Depression, between the two world wars — when there was an inward turning to American problems and American culture, and Grant Wood was at the forefront, celebrating local culture for what it was, what it had been, and what it could be.”

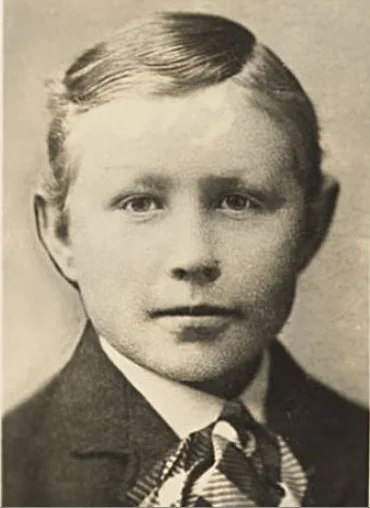

Young Grant Wood

Today, American Gothic remains one of the most recognized paintings in the world. Even if people don’t know Grant Wood by name, they know his work — and they know it represents something deeply American, and deeply Iowan.

Formative years and Regionalism

Born in 1891 near Anamosa, Iowa, Wood moved to Cedar Rapids at age 10 after the death of his father.

There he nurtured a passion for drawing and painting while also exploring craftsmanship through metalsmithing, jewelry-making, and furniture design. His artistic education took him from the Handicraft Guild in Minnesota to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Upon returning to Cedar Rapids, Wood taught art in the public school system and spent four summers in Europe, where he studied Impressionism and searched for his own artistic voice.

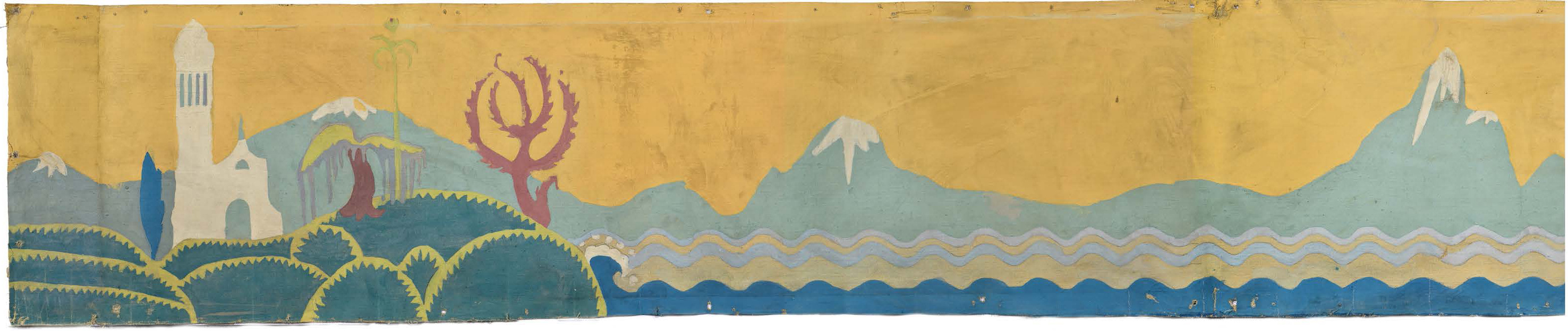

Grant Wood and McKinley Junior High School students, detail of Imagination Isles, in the 1920s. Cedar Rapids Community School District, Iowa; on loan to the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, Iowa.

Turning point for Wood’s Regionalism style

That voice came into focus in the 1930s, as Wood embraced Regionalism and his Iowa upbringing. His early Regionalist works, including Stone City, Iowa (1930) and Young Corn (1931), reflect a profound connection to the land and its stories.

Stone City, 1930. Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska; gift of the Art Institute of Omaha 1930.35.

“Wood went through a version of American Impressionism, with very broad brush strokes, which is quite different than his mature style that started right around 1930 with American Gothic. He became the national spokesperson for Regionalism. Although it usually is associated with the American Midwest, the movement was broader and based on the principle that it was important as an artist to be authentic to your own place and your own identity.”

Joni Kinsey, professor emerita in the UI School of Art, Art History, and Design

Creating culture and community

Grant Wood often hosted prominent artists and authors in Iowa City, in his home at 1142 East Court Street, and at the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Speakers (located on the second floor of the current Prairie Lights Books in Iowa City).

Grant Wood and author Carl Sandburg over tea in Wood's home at 1142 East Court Street in Iowa City, circa 1940.

Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton, a prominent American Regionalist artist, in Iowa City, Iowa.

Creative impact at the University of Iowa

The success of American Gothic catapulted Wood into the national spotlight. With a $300 prize from the Art Institute of Chicago and widespread acclaim, he became a sought-after speaker and a symbol of American art rooted in place.

In 1934, he was appointed Iowa director of the Public Works of Art Project, a New Deal initiative that employed artists to create public murals and sculptures. Wood oversaw the creation of the murals for the Iowa State University library, earning praise from The New York Times.

Recognizing his growing stature, University of Iowa leaders invited Wood to join the faculty. He accepted a position in 1934 and settled into a home he lovingly restored at 1142 E. Court St.

During this time, he was a prolific artist, painting Death on the Ridge Road (1935), Parson Weems’ Fable (1939), and Spring in Town (1941) and creating a series of lithographs and book illustrations while also mentoring a new generation of artists.

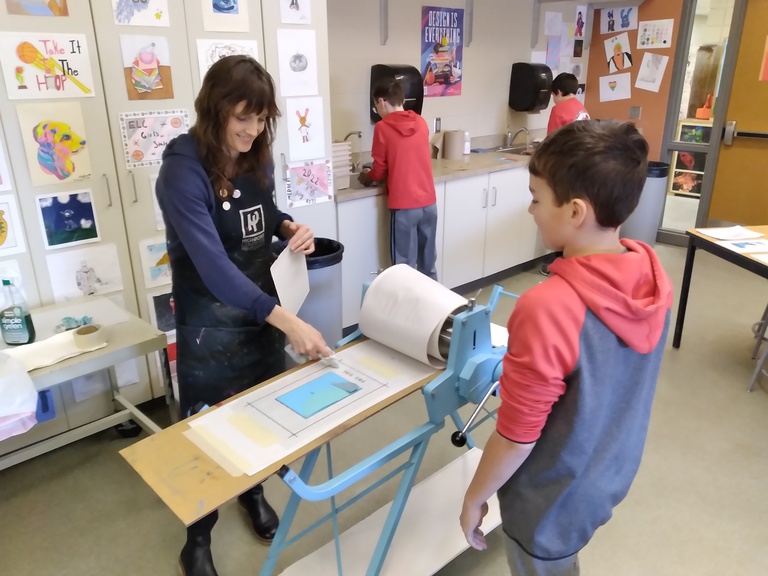

Students painting on scaffolding; Grant Wood in foreground talking with visitors of his makeshift studio set up in an empty swimming pool in Halsey Hall on the University of Iowa campus. These murals were painted with Wood's direction as part of the Public Works of Art Project in the 1930s, and are now displayed at the Iowa State University Library.

A look at the creative process

Like many artists, Grant Wood used models to help shape his paintings to portray realistic life.

Grant Wood crafting what will later become his Spring in Town painting with a model posing for the image.

Spring in Town, 1941. Swope Art Museum, Terre Haute, Indiana 1941.30

Mentoring a new generation of artists

Among his students was pioneering sculptor Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012), one of the first students in the U.S. to earn an MFA — and the first Black woman to receive the degree. She credited Wood with encouraging her to embrace her identity and tell stories rooted in her own experience, an ethos that shaped her powerful depictions of Black women and the Civil Rights Movement.

Grant Wood's art clinic in Seashore Hall on the University of Iowa campus, where students learned from and worked alongside Wood.

Tensions, illness, and a premature farewell

While Wood found creative fulfillment in Iowa City, his time at the university was not without challenges. A philosophical clash with department head Lester Longman (1905–87), an East Coast–educated art historian and an advocate of Modernist art, created ongoing tension. Longman viewed Wood’s Regionalism as provincial, while Wood saw Modernism as disconnected from the American experience.

The conflict escalated to the point where Wood considered resigning. University administrators intervened, offering him a sabbatical and removing him from Longman’s supervision. Just as a resolution promised to dampen the feud, Wood was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Wood died in February 1942, just one day before his 51st birthday, his final years marked by both artistic productivity and personal strain.

Grant Wood's experience at the University of Iowa

Joni Kinsey, professor emerita in the School of Art, Art History, and Design, talks about Grant Wood's experience at the University of Iowa in this talk commemorating Grant Wood's 125th birthday. The presentation was part of the University of Iowa Museum of Art's Social (In)Justice exhibition in 2016.

Honorary Degree, 1938, lithograph, Stanley Museum of Art, Iowa City; Gift of Edwin B. Green

“We’re not just preserving history, we’re building on it by giving artists the space and support to carry forward Wood’s spirit of creativity, craftsmanship, and community.”

Jim Hayes, founder of the Grant Wood Legacy Program at the University of Iowa

A vision reimagined

Though Wood’s influence faded after his death, and his name became disassociated with the University of Iowa, his vision never truly disappeared. In 1975, Iowa City attorney and 1963 Iowa law graduate Jim Hayes purchased Wood’s former home at 1142 E. Court St. in Iowa City. As he restored the house, Hayes developed an appreciation for Wood’s work and philosophy.

That appreciation blossomed into action. In 2009, Hayes founded the Grant Wood Legacy Program at the University of Iowa, and in 2011 established the Grant Wood Art Colony, both in public-private partnership with the University of Iowa. The colony, which consists of five houses adjacent to the Court Street property, is a vibrant community where artists live, create, and teach. The Grant Wood Legacy Program and the Grant Wood Art Colony host a biennial symposium, public events, and a prestigious fellowship program.

Each year, three fellows — one each in painting and drawing, printmaking, and interdisciplinary performance — are selected to live at the colony and contribute to the university’s arts campus. The colony also supports scholarship through the Grant Wood Catalogue Raisonné, an ongoing digital archive of his complete works.

Beneath the satire lies something deeper:

a reflection of American identity.

The enduring power of American Gothic

Few works of art have captured the American imagination quite like American Gothic, which is housed at the Art Institute of Chicago. According to Sotheby’s Institute of Art, it’s the fourth most Googled artwork in the world. Its power, explains Kinsey, lies in its adaptability.

“That image seems to represent America — not just of the 1930s, but of any era. It’s malleable. It’s transformable to any given moment of American culture. It has humor. It has seriousness. And that’s part of the genius of that work.”

Indeed, the painting has inspired countless parodies, from magazine covers, to political cartoons, to Halloween costumes. Yet beneath the satire lies something deeper: a reflection of American identity. The couple’s solemn expressions, the Gothic window, the pitchfork evoke a sense of resilience, tradition, and quiet strength.

In that way, American Gothic is more than a painting. It’s a mirror, one that continues to reflect who we are, where we’ve been, and where we might be going.